Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Palaeoecology

Archaeobotanical analysis of plant macroremains

This specialization is based on the finding, separation and determination and evaluation of botanical macro-remains from different contexts of archaeological sites. A lot of layers and archaeological fills are situated on common "dry" sites with prehistoric and early medieval settlement and burial places. An important part of the analysed features are situated in permanently wet positions, like for example wells, cesspits, water systems, cellars and so on. The investigated objects are usually plant seeds and their fragments, but also needles, chaff and the remains of straw. It is possible to evaluate which useful plants were used or collected on the basis of a determination of the plant structure (cereals, legumes, fruits, vegetables, spices, technical plants) and not only this: in accordance with the natural plant species structure it is possible to roughly reconstruct the immediate vicinity of an archaeological site (arable fields, meadows, waste areas, wetlands, forests, woods and shrub formations.

Mulberry (Morus nigra), found in Ústí na Labem in a medieval well. Photo by V. Komárková

The nature of the information is particularly important for archaeologists, because it is the main subject of any palaeoeconomical reconstruction. Based on macro-remains analyses it is possible to observe processes of cereal domestication in prehistory and indirectly the development of archaic systems of agriculture. Within the setting of a specific site relations between cultivated and collected plants are also visible. The spatial analysis of archaeobotanical macro-remains is also very attractive to archaeologists, e.g. the distribution of different species on larger archaeological sites etc. Today, larger sets of captured plants are evaluated by multivariate data analysis, which helps to find hidden information in them.

In paleoecological studies, the importance of macroresidue analysis lies primarily in its local character, in contrast to the results of anthracological or pollen analysis.

Carrot bur parsley (Caucalis plytycarpos) found in Ústí na Labem in a medieval well. Photo by V. Komárková

Wells, sumps, swamps – macro-residual treasure troves

A moist environment without access to air is extremely suitable for preserving organic material, i.e. also plant macro-residues. Thanks to it, even those parts of plants that would otherwise perish (soft seeds or whole fruits, leaves, etc.) can be preserved. Wells or sumps also have the advantage that a variety of waste (kitchen, fecal, production, etc.) was intentionally deposited in them. Therefore, we find in them macro-residues in high concentrations, which give us relatively detailed information about what people used to eat in the past, where the hay they fed their cattle came from, and so on. On the other hand, the damp fillings of ditches or blind branches of rivers inform us more about how the nature around them has changed over the ages.

In the younger stages of European prehistory, the analysis of macro-residues can capture the influences of classical Roman agriculture. Significant changes in the structure of agricultural production can be observed on the border between the early and high Middle Ages, but also at the beginning of the modern age. In certain cases, the analysis of plant macro-residues can capture very rare finds of imported plant species, such as nutmeg, fig tree or black pepper. Among wild plant species, once common, now very rare plants, such as cattails, sometimes appear in the analyzed material. Today, larger sets of captured plants are evaluated by multivariate data analysis.

Methodology

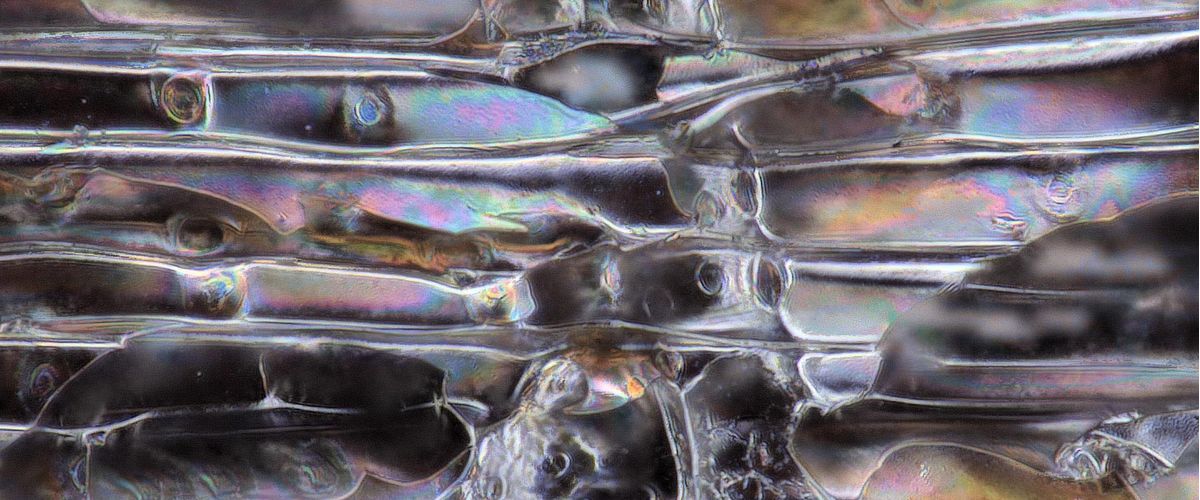

Soil samples are usually collected in plastic bags (as a general rule, the more the merrier). They are then washed through sieves and dried. Finally, plant macro-residues are selected and determined in them under a stereoscopic magnifying glass. Almost all types of archaeological deposits are suitable for capturing plant macro-remains. The basic method of separation is flotation. However, there is a big difference in the concentration of plant macro-residues per certain volumetric unit of sediment. In prehistoric objects of "dry" localities (Neolithic building pits, reservoirs, semi-earthen pits, etc.), a large volume of soil must be washed away in order to obtain a numerically representative sample of macro-residues (the recommended minimum is the analysis of 100 liters of deposit or fill). For these large volumes, the flotation method is used. Its principle is the melting and dilution of the deposit material in larger containers. Plant macro-residues float to the surface of the water. This solution is then poured through a set of sieves, usually with mesh diameters of 1 mm and 0.4 mm. Dry sieving is used for particularly dry and sandy deposits.

On the contrary, we can expect a high concentration of plant macro-residues in some fillings of prehistoric, but especially medieval and modern objects, such as wells, fecal pits, or wet ditches. Other separation methods are used here, based on a system of sieves, with the help of which the studied sediment is sorted into dimensional fractions and analyzed under a microscope, including the inorganic component. For such concentrated deposits, it is usually sufficient to analyze 2-5 liters of material.

Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum), found in Ústí na Labem in a medieval well. Photo by V. Komárková